Landscape Analysis of Women-Owned Businesses in Government Contracting

Introduction

In Fiscal Year (FY) 2024, the National Women’s Business Council (NWBC) contracted the Library ofCongress Federal Research Division (FRD) to examine the experiences of women-ownedbusinesses (WOBs) as potential vendors and study whether the Women-Owned Small Business(WOSB) Federal Contract Program has increased WOB and WOSB participation in governmentcontracting.

This document provides preliminary findings on WOSB federal contracting trends. These findingsinclude the federal contracting world in general, existing complications within the WOSB FederalContract Program, and available data sources related to WOBs’ and WOSBs’ federal contracts. ThisInitial Findings Report is composed of two main sections: the Literature Review and Data Review.Findings from this report will inform the creation of the mixed-methods study on the experienceof participating in and the effectiveness of the WOSB Federal Contract Program (hereafter alsoreferred to as the WOSB Program within this report).

1.1. Research Questions

In examining the literature, FRD sought to answer the following questions:

- What does the literature say specifically about how the WOSB Program operates ascompared to other similar programs that purport to offer access to government contracts?

- How does the process of finding, competing for, and fulfilling government contract awardsdiffer for WOSB vendors when compared to non-WOSB vendors?

- What does the literature say about structural and interpersonal WOBs may encounterwhen seeking government contracts?

In exploring available datasets related to federal contracting, FRD endeavored to find sources thatcould help answer the following questions:

- Has WOSBs’ share of non-set-aside contracts increased as the share of set-aside contractshas increased?

- Do firms that win set-aside contracts tend to go on to do increasing volumes ofgovernment business and/or win non-set-aside contracts?

- Are there meaningfully different trends in subsequent survival and growth betweenbusinesses that do and do not secure certification/win set-aside contracts?

1.2. Methodology

FRD reviewed academic journal articles, government reports, and other grey literature for theliterature review portion of this document. The scholarly journals FRD reviewed focused on topicsrelated to WOSBs and federal contracting. Among the databases that FRD consulted wereSageJournals, JSTOR, ProQuest, EBSCOhost, and the Library of Congress’s Primo database.Government agencies from which FRD reviewed grey literature included the GovernmentAccountability Office (GAO), Congressional Research Service (CRS), Small Business Administration(SBA), and the Minority Business Development Agency (MBDA). Keyword searches included acombination of the words listed in Table 1.

To extend the search beyond using keyword searches in databases, FRD also utilized the“snowballing” method, which involves reviewing relevant sources located in the reference sectionof a source. To search for potential data sources for use in the following phase of this study, FRDsnowballed sources from relevant studies discovered from the review of the literature.

1.3. Key Terminology

FRD compiled a list of key terms and their respective definitions in this subsection. These termsare frequently used within federal contracting and throughout this report. Vendors refer to thebusinesses (also known as firms or contractors) that supply goods and services to the federalgovernment. A Contracting Officer (CO) is an individual from a federal agency that oversees thesolicitation, awarding, and management of the contract.1 This report considers prime contractsand subcontracts.

- Prime contracts exist when a contract is made directly between the federal agency andthe vendor. The vendor would be known as a prime contractor.

- Subcontracts occur when the prime contractor subcontracts out some portion of thecontract to another vendor. The vendor would be known as a subcontractor.

The three types of contract solicitations (or request for offers from businesses) this reportconsidered are listed below.

- Solicitation occurs through full and open competition when the CO is certain that norestrictions to the award apply.* The award is open for competition between all eligiblefederal vendors.4▪

- Solicitation through a set-aside occurs when the CO restricts competition to a limitedgroup of business types. 5 For example, a CO can set-aside a contract to just WOSB vendorsif at least two WOSB vendors can fulfill the contract. All eligible WOSB vendors thencompete for the contract, thereby restricting but not eliminating all competition.▪

- Solicitation through sole-source or sole-source authority occurs when the COdetermines that only one specific vendor can fulfill a contract.6 For example, a CO can usesole-source authority to award a contract to a WOSB if they are able to determine that noother WOSB vendor is able to fulfill the award, regardless of whether non-WOSB vendorsare available to fulfill the award. This award would then no longer be competitive.

LITERATURE REVIEW

This section presents findings from a review of existing literature on the WOSB Federal ContractProgram and other similar federal contracting programs. The literature review explores the typicalprocess for federal contracting, a history of the introduction of the WOSB Program, what theprogram and similar programs entail, WOSB contracting rates, and potential complicationspreventing WOSBs from federal contracting.

2.1. Federal Contracting Programs

This subsection begins by establishing the federal solicitation process, as well as that of programssimilar to the WOSB Federal Contract Program and administered by SBA. The subsection goesinto further detail on the WOSB Federal Contract Program and how agencies can restrictcompetition to fulfill federal obligations.

2.1.1. Full and Open Competition

Under 15 U.S.C. § 644, the federal government is required to award at least 23 percent of the totaldollar value of all prime contract awards to small businesses within each fiscal year. More specificgoals also exist for small businesses owned by service-disabled veterans, socially and economicallydisadvantaged individuals, and women, along with businesses located in historically underutilizedbusiness zones (HUBZones). Service-disabled veteran-owned small businesses (SDVOSBs), smalldisadvantaged businesses (SDBs), and WOSBs each have a government-wide goal of at least fivepercent of the total dollar value of all prime contracts and subcontracts awarded annually. SDBprograms include the 8(a) Business Development Program, which also trains and providestechnical assistance on federal contracting.* The HUBZone government-wide goal consists of atleast three percent of the total dollar value of all prime contract and subcontract awards. Eachgoal comprises the sum of federally awarded dollars to both prime and subcontracts. 7 SBAoversees certifying and providing resources to each of these business groups. The agency servesconsults for each federal agency to help establish and negotiate individual agency goals. SBA alsotracks and administers the government-wide contracting rate goals for each business type.

While there are many ways of soliciting contracts, “full and open competition” is typically thepreferred and standard form of federal contract solicitation.9 Full and open competitive contractscomprise awards open to all qualified federal vendors. Of all the bidders a contract solicitation may receive, the federal agency can choose a vendor that best fulfills its needs based on technicaland monetary aspects. 10 The introduction of WOSB, SDVOSB, SDB, and HUBZone programsensured that competition can be restricted to specific vendor types rather than through a full andopen competition between all eligible vendors.

2.1.2. WOSB Federal Contract Program

In 1994, Congress enacted the Federal Acquisition Streamlining Act (FASA) to minimize federalcontracting requirements and simplify the federal acquisition process.12 FASA increased the awardgoal for WOSBs to at least five percent of all federal government contracting dollars from theoriginal goal of one percent, which was set in the 1970s.13 Congress also introduced the SmallBusiness Reauthorization Act of 2000 with the hopes of clearly defining and establishing theWOSB Program. To meet the government-wide goal of five percent and permit an agency’s COthe ability to easily award WOSBs contracts, the act proposed providing COs with the power torestrict competition for the solicitation of federal goods to small businesses owned and controlledby women.

The WOSB Federal Contract Program was officially created after the issuance of an SBA final rulethat became active on February 4, 2011. This final rule granted SBA oversight over the program.Through this final rule, COs were granted the power to restrict competition to WOSB vendors—including EDWOSBs, a subset of WOSBs—using set-asides.15 In other words, rather than allowingfull and open competition with all eligible vendors, COs can “set aside” the contract to restrictcompetition to only WOSB vendors as long as more than one WOSB vendor was able to competefor the contract. In addition to WOSB set-asides, SBA introduced a 2015 final rule that permittedCOs the ability to call upon sole-source authority. Sole-source authority allow COs to award acontract to a single WOSB vendor, given that no other WOSBs can fulfill the contract requirementsand needs.16 Therefore, regardless of whether non-WOSBs vendors can fulfill a contract, a CO canuse set-asides or sole-source authority to restrict the competition to exclusively WOSBs.

SBA issued another rule in 2020 implementing the requirement of SBA certification of WOSB andEDWOSB potential vendors. Previously, vendors were not required to go through an officialcertification process to ensure eligibility for the WOSB Program. With this rule in place, WOSBsand EDWOSBs must either be certified through SBA’s official certification program or through anSBA-approved Third-Party Certifier.17 Implementing this process ensures that the WOSB Programis restricted to just WOSBs and EDWOSBs, thereby strengthening the integrity and SBA oversightof the program.

2.2. WOSB Contracting Trends

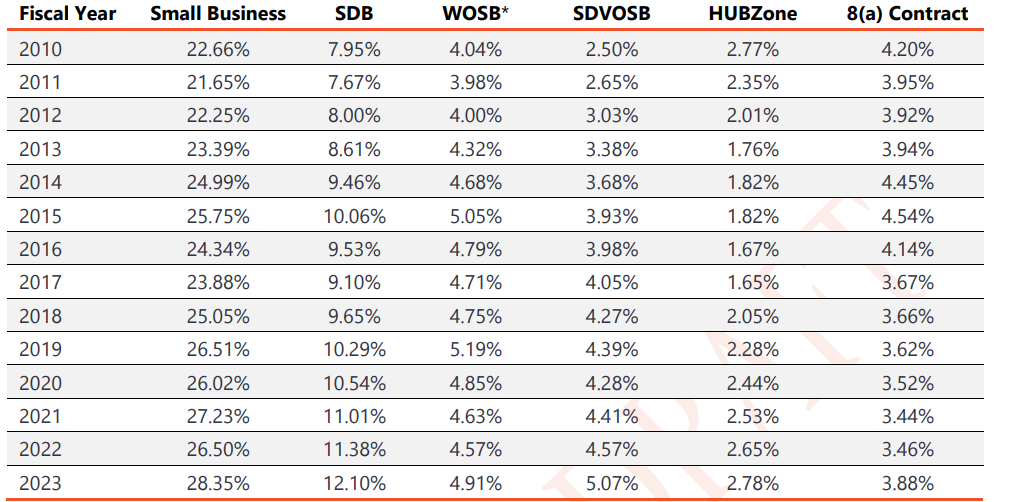

The government-wide goal of five percent has only ever been attained twice since the inceptionof the WOSB Program—once in 2015 with 5.05 percent and a second time in 2019 with 5.19percent of all federally awarded contract dollars.19 Even though the government consistently failsto meet the five percent goal, WOSB percentages tend to be higher when compared to SDVOSB,HubZone, and SDB programs. Section 3.2 provides detailed statistics on the percentages of federaldollars awarded to different SBA programs and the proportion of WOSB awarded dollars basedon solicitation type.

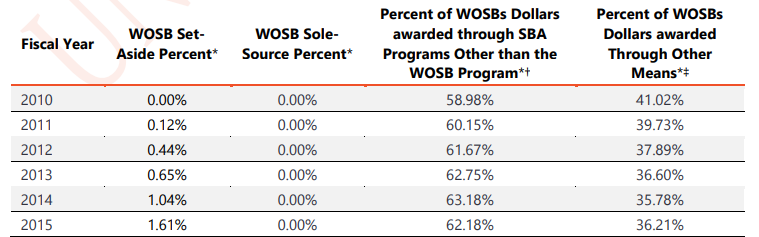

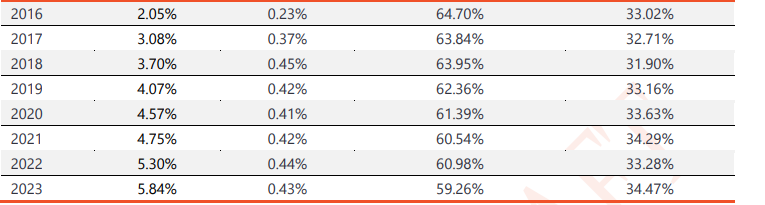

Since the introduction of WOSB set-asides in 2015, the use of set-asides increased from 0.62percent in 2014 to 1.13 percent of all awarded WOSB contract dollars the following year. Thepercentage of contract dollars awarded through the WOSB set-aside program has steadilyincreased, reaching 5.65 percent of all WOSB awarded dollars in FY 2023. WOSB contract dollarsawarded through sole-source authority remained at an average of about 0.35 percent of all federalcontract dollars from its introduction in FY 2016 to FY 2023.20 Even then, set-asides and solesource contracts only make up a small portion of all WOSB awarded contracts. In FY 2018, 63percent of all contract dollars awarded to WOSBs were solicited through full and open competitionrather than through the procurement vehicles offered by the WOSB Federal Contract Program.Furthermore, 33 percent of award contract dollars were through other programs such as the 8(a)and HUBZone programs. Only four percent of contract dollars were awarded directly through theWOSB Program. As determined from the General Services Administration (GSA) FederalProcurement Data System Report (FPDS), a majority of WOSB awards come from full and opencompetition or through small business preferences.

Statistics show that the Department of Defense (DOD) is one of the few federal departments thatalmost consistently meet the annual five percent WOSB contracting goal.22 In FY 2023, six of thetop ten agencies that awarded contract dollars to WOSBs fell under the DOD. Three of the othertop agencies fell under the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and one under theDepartment of the Treasury.23 Overall, studies have found that large federal departments oragencies, such as the DOD, are more likely to award contracts to WOSBs over other vendor types.

Studies show that disparities exist between the proportion of awarded federal dollars and theproportion of small businesses available. For instance, in FY 2020, minority-owned businessesreceived 9.4 percent of federal contract dollars while making up 18.4 percent of all U.S. businessesin 2019. WOSBs were awarded 4.9 percent of federal contract dollars in 2020 while making up20.9 percent of all businesses in 2019. More generally, WOBs received a little over five percent ofcontract dollars while making up 23 percent of all businesses.

While these numbers may seem low, actual dollar amounts awarded through a specific programmay be even lower. Agencies can award a WOSB vendor under a different program that theyqualify for, yet still include that contract amount as a part of its goal for the WOSB Program. Forexample, a WOSB eligible vendor may win a contract under an 8(a) set-aside. The federal agencymay “double count” the contract value under both their 8(a) and WOSB goals. However, thispractice results in the conflation of the percentage of dollar value of contracts that were actuallyawarded through the WOSB Program. Double counting allows for percentages to seem higherthan they actually were.26 This caveat further contributes to the disparity between the percentageof dollars federally awarded WOSBs and portion of businesses owned and operated by women.

2.3. Structural and Interpersonal Choices that Inhibit WOSB Contracting

MBDA performed a regression analysis in 2022 to study the probability of different smallbusinesses winning federal contracts. Daniel Chow, MBDA’s Senior Economist, found that“woman-owned, minority-owned, and other veteran-owned firms have lower odds than otherfirms to win a contract, all else being equal.” Chow also found that the odds of these firms winninga contract without participating in the 8(a) program is 37 percent lower than firms who are in the8(a) program.27 MBDA also found that firm size, age, and security clearance were associated withhigher odds of winning a contract, along with a number of other factors.28 These findings areechoed in the RAND Corporation’s 2007 paper, “The Utilization of Women-Owned SmallBusinesses in Federal Contracting,” which utilized data from the GSA’s FPDS and the 2002Census.29 The authors found that “the conclusion that WOSBs are underrepresented in someindustries is not dependent on the possible error in the definition of small firms in the FPDS” andthat WOSBs were found to be either underrepresented or substantially underrepresented in thedata. 30 Business that are under the HUBZone program, are socially disadvantaged, or haveserviced-disabled veteran owners are also more likely than other small and minority-ownedbusiness to receive federal contracts.31 These findings indicate that WOBs, in general, are less likelyto be awarded federal contracts without participation in certain programs.

Studies also show that small and diverse businesses are more likely to receive contracts of lesscomplexity. Mikaella Polyviou, Leopold Ried, and Robert Wiedmer, procurement and supply chainmanagement scholars at Arizona State University and the University of Melbourne, performed astudy in 2024 on the effectiveness of set-asides for small and diverse vendors. The authors foundthat SDB and other minority businesses were less likely to win science, technology, engineering,and mathematics (STEM) related contracts. At the same time, the use of set-aside solicitations hasshown to increase the likelihood of SDBs receiving complex or STEM-heavy contracts.32 Similarly,Chris Parker and Dwaipayan Roy, professors at the Darden School of Business at the University ofVirginia, found that the “prevalence of gender and racial disparities in the awarding of federal contracts is well-acknowledged.” The authors also found that, in addition to the lower probabilityof being awarded, MOBs’ federal contracts are “characterized by lower average median pay levels.”However, Parker and Roy believe that the lack of granular data makes it difficult to addresspotential structural barriers.

Other studies have attempted to understand structural barriers by performing surveys and casestudies of WOSB vendors and their experiences. The low percentage of contract dollars awardedto small and minority-owned businesses and inability to consistently meet government-widegoals can be attributed to systemic and discriminatory barriers. SBA’s 2023 study on equity withinfederal contracting found that small businesses, especially those owned by socially disadvantagedor historically marginalized groups, face more obstacles than others. These obstables preventedthese businesses from pursuing federal contracts.34 Barriers affecting the vendors include:

- Disproportionate lack of access to capital, often provided at elevated interest rates;

- Discriminatory attitudes among and manipulation by actors in the contracting process;

- Time and burden required for certification and to access small business programs;

- Complicated and time-consuming procurement processes, and demanding bonding, priorexperience, and other technical pre-requisites, that new and small businesses can’tnavigate or meet as well as incumbent providers can;

- Exclusion from professional networks and communications channels where businessopportunities are promoted;

- The practices of delayed payment for services and lengthy negotiation over contracts thatare untenable for small businesses without significant cash reserves; and

- Other practices that demand capabilities small and disadvantaged businessesdisproportionately lack, like ability to accept government credit cards.

In addition to the listed obstacles above, other studies—such as a 2022 study by Florida StateCollege business professors, Justin Bateh, and Shawna Coram, and a 2012 study by professors ofpublic service and policy, Sergio Fernandez, Deanna Malatesta, and Craig R. Smith—also studiedand attributed psychological aspects of gender bias to explain the disparities within federalcontracting.

SBA also found that federal agency procurement operations are organized in ways that limitopportunities for WOSBs and other business types. Barriers on the federal agency side include:

- Limited agency capacity and capability for procurement;

- Negative agency staff perceptions of the complexity of procurement programs; and

- Declining availability of qualified vendors.

Given that a multitude of small business programs exist, federal agencies may lack the resourcesto support each one. This phenomenon may contribute to procurement and program staffoverlooking the WOSB program, especially if federal agencies are not held accountable for failingto meet the procurement goals. Furthermore, agencies have difficulty discovering vendors due tothe lack of gender-disaggregated vendor data and due to the shrinking pool of WOB vendors.38Based on a 2023 report from the Bipartisan Policy Center, the number of small businesses availablefor government contracting decreased by 38 percent from 2010 to 2019.39 In general, federalagencies are unfamiliar with the WOSB Program and what it entails.40 All of these complicationsappear to impact federal agencies’ award decisions, and impede the WOSB Program andbeneficial competition for government business.

3. DATA

This section explores potential data sources related to federal contracting that may be useful inthe design and implementation of a study analyzing the effectiveness of the WOSB Program. FRDidentified four data sources that can help examine and explain disparities between WOSBs andother businesses within federal contracting. This section also discusses the preliminary trendsfound based on aggregated data provided in the Small Business Data HUB, a database compiledby SBA to track government agencies’ achievements of SBA program goals.

3.1. Data Sources and Methodologies

FRD identified several data sources that can explain or quantify disparities in governmentcontracting between WOSBs and other businesses. These data sources include USASpending andSBA’s System for Award Management (SAM) database. USASpending tracks the lifecycle of federalfunds after they are awarded. This database contains the amount, type, and period of performancefor each contract, along with details about the recipients and subcontractors fulfilling eachobligation.41 The database also encompasses several relevant variables for identifying trends incontracting, including details about the business involved in each contract. USASpending providesa total of 127 variables that describe the characteristics of each company involved in a federalcontract. These include ownership characteristics such as the sex and race, along with the firm’ssize, location, whether the business is considered economically disadvantaged, and many otherconsiderations.

The USASpending database also provides variables for identifying WOBs and WOSBs. Theseinclude true/false variables like “WomanOwnedBusiness” and “WomenOwnedSmallBusiness,”which define whether the selected contractor is a WOB or WOSB. These variables can also bederived from the SAM data variable “Business Types.”42 Not only can these categorical variablesbe used to distinguish broad trends in contracting across different categories of WOBs, but alsoacross other types of businesses to provide a basis of comparison. In addition to firm attributes,USASpending provides information at the award level, including whether a contract is a “FairOpportunity” or “Limited Source,” which explains the level of competitiveness of a contract. Thereare also variables that indicate whether a contractor is an 8(a)-program recipient among otherspecifications, many of which come from GSA’s FPDS.

While USASpending focuses on individual awards and transactions over time, the SAM databasefocuses on contractors who are eligible to win federal funds. The database “unifies thegovernment-wide award management systems” and allows users to view vendors that are eligibleto do business with the federal government. 44 The SAM data could be used to distinguish what portion of eligible federal contractors are WOSBs or WOBs compared to the general population.FRD hopes to use this database to contextualize which vendors ultimately win contracts inUSASpending compared to the group of vendors that are eligible to compete. This data couldfurther explain differences in contracting outcomes by not only comparing which entities receivedfederal funding, but also what portion of the total eligible entities are WOSBs. This would providea basis of comparison between the portion of funding that WOSBs receive compared to theportion of total federally eligible entities that WOSBs represent. These findings would quantifydisparities, if any, between different business types within federal contracting.

The final data sources that FRD identified are the Census Bureau’s ABS (Annual Business Survey)and ACS (American Community Survey) databases. The ACS is updated on a yearly basis and isfreely accessible. The ABS is also updated yearly and includes statistics related to all “nonfarmemployer businesses filing the 941, 944, or 1120 tax forms.” The ABS also provides informationabout business owner characteristics, including sex, race, ethnicity, veteran status, and publicholding.45 The data in the ABS could be used to establish a baseline for the portion of businessesthat are WOBs and WOSBs based on the portion they represent in tax filings. This would furthercontextualize the portion of federal award recipients that are WOSBs, as it allows FRD to accountfor the portion of WOSBs that receive contracts, the portion of firms that are eligible to receivefederal contracts under the WOSB Program, and the portion of WOSBs compared to all firmseligible to receive federal contracts.

The ACS could provide context on WOSBs by estimating what portion of the workforce consist ofwomen.46 The ACS data includes tables of broad employment characteristics at the aggregatelevel, which can be used to explain the relative portion of WOSBs in the economy by identifyingwhat portion of workers are women. The ACS data could allow FRD to establish a baselineunderstanding of women’s employment to determine if WOBs make up a lower portion comparedto the portion of women employed. ACS data could also reveal portions of federally eligiblebusinesses and businesses that received federal funding.

3.2. Preliminary Trends

Based on the Small Business Data HUB, the proportion of federal dollars awarded to WOSBs tendsto be higher than that of SDVOSB, 8(a), and HUBZone vendors, despite failing to consistently meetthe five percent goal. The percentage of federal dollars awarded to SDB-owned contractsconsistently remains higher than that of all other SBA federal contract programs. As seen in thetable below, the government only met the WOSB Program goal in FY 2015 and FY 2019. TheSDVOSB, HUBZone, and 8(a) contract programs have similarly failed to meet their respective goals,excepting SDVOSB in FY 2023 (at 5.07 percent of all federally awarded contracts).

Table 2. Percentage of Federal Contract Program Dollars Awarded from FY 2010 to 2023

Even with the introduction of set-asides for WOSBs in 2011 and sole-source authority in 2015, theuse of set-asides and sole-source as solicitation methods remain strikingly low compared to otherWOSB solicitation methods (see Table 3). The percent of federally awarded dollars to WOSBsthrough other SBA programs makes up an average of about 60 percent, from FY 2010 to FY 2023.The second highest solicitation method by dollar amount comprise WOSBs awarded throughother means (which includes non-SBA programs and full and open competition), with an averageof about 35 percent of all WOSB awarded dollars. In comparison, WOSB contracts awardedthrough set-aside solicitation reach up to five percent of all WOSB awarded dollars, while solesource solicitation remains below 0.5 percent of all WOSB awarded dollars.

Table 3. Percentage of Federal Dollars Awarded to WOSBs

Federal agencies are electing to use other programs or methods of solicitation over the WOSBProgram’s set-asides and sole-source methods. As previously discussed, this could be due to alack of accountability or familiarity with the WOSB Program on the federal agency side. Thepractice of double counting may also make these percentages appear higher than they actuallyare.

4. NEXT STEPS

In this Initial Findings Report, FRD examined existing literature on the WOSB Federal ContractProgram and WOSB experiences to gain an understanding of existing disparities withingovernment contracting. FRD also ventured to understand the process of federal contracting andhow a firm or vendor under SBA contracting programs may differ in award competition. Thisbackground research provides a basis for the creation of a study that explores WOB and WOSBexperiences as government vendors and the effectiveness of the WOSB Program. The preliminaryfindings from this report will inform the design of the study. In its next steps, FRD will present thefindings gathered from the review of the literature and data and draft a Study Design, which willpropose the methodology for the qualitative and quantitative analysis portion of the study.

5. NOTES

1 Responsibilities, 48 C.F.R. § 1602-2 (November 25, 2024), https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-48/chapter-1/subchapterA/part-1/subpart-1.6/section-1.602-2.2 Definitions, 48 C.F.R. § 3.502-1 (November 25, 2024), https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-48/chapter-1/subchapterA/part-3/subpart-3.5/section-3.502-1.3 Definitions, 48 C.F.R. § 3.502-1 (November 25, 2024), https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-48/chapter-1/subchapterA/part-3/subpart-3.5/section-3.502-1.4 Full and Open Competition, 48 C.F.R. § 6.1 (December 1, 2022), https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-48/chapter1/subchapter-B/part-6/subpart-6.1.5 General, 48 C.F.R. § 19.501 (November 25. 2024), https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-48/chapter-1/subchapter-D/part19/subpart-19.5/section-19.501.6 Sole Source, 48 C.F.R. § 19.811-1 (November 25, 2024), https://www.acquisition.gov/far/19.811-1.7 Awards or contracts, 15 U.S.C. § 644 (2008).8“Agency Contracting Goals,” U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA), last updated March 18, 2024,https://www.sba.gov/document/support-agency-contracting-goals; “Small Business Data Hub,” U.S. SBA, accessedDecember 2, 2024, https://datahub.certify.sba.gov/.9“14 FAH-2 Contracting Officer’s Representative Handbook,” U.S. Department of State, accessed December 2, 2024,https://fam.state.gov/fam/14fah02/14fah020220.html.10 Full and Open Competition, 48 C.F.R. Subpart 6.1 (December 1, 2022), https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-48/chapter1/subchapter-B/part-6/subpart-6.1.11 “Women-Owned Small Business Federal Contract Program,” U.S. SBA, last updated July 2, 2024, sba.gov/wosb;“Veteran Contracting Assistance Programs,” U.S. SBA, last updated November 22, 2024, sba.gov/sdvosb; “SmallDisadvantaged Business,” U.S. SBA, last updated August 22, 2024, https://www.sba.gov/federalcontracting/contracting-assistance-programs/small-disadvantaged-business; “HUBZone Program,” U.S. SBA, lastupdated July 18, 2024, sba.gov/hubzone.12 Federal Acquisition Streamlining Act of 1994, Pub. L. No. 103-712, Title I, Subtitle A, 108 Stat. 3243 (1994).13 R. Corrine Blackford, The Women-Owned Small Business Contract Program: Legislative and Program History, CRSReport for Congress R46322, (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service [CRS], June 2024).14 Small Business Reauthorization Act of 2015, H.R. 5667, 106th Cong. (2000); Kathleen Mee, "Improving Opportunitiesfor Women-Owned Small Businesses in Federal Contracting: Current Efforts, Remaining Challenges, and Proposals forthe Future," Public Contract Law Journal 41, no.3 (2012): 721-743, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41635352.15 Rachel Herrington, "Five Years in: A Review of the Women-Owned Business Federal Contract Program," PublicContract Law Journal 54, no. 2 (2016): 359-82, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26419510; Women-Owned SmallBusiness Federal Contract Program, 75 Fed. Reg. 62258 (October 7, 2011); David N. Beede and Robert N. Rubinovitz,Utilization of Women-Owned Businesses in Federal Prime Contracting: Report Prepared for the Women-Owned SmallBusiness Program of the Small Business Administration (Washington, DC: Office of the Chief Economist Economics andStatistics Administration, December 2015).16 Government Accountability Office (GAO), Women-Owned Small Business Program: Actions Needed to AddressOngoing Oversight Issues, GAO-19-168 (Washington, DC: GAO, March 2019), https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-19-168.17 “Women-Owned Small Business Federal Contract Program,” U.S. SBA, last updated July 2, 2024, sba.gov/wosb.18 Office of Advocacy., “SBA Final Rule: Women-Owned Small Business and Economically Disadvantaged WomenOwned Small Business Certification,” SBA Office of Advocacy, May 11, 2020. https://advocacy.sba.gov/2020/05/11/sbafinal-rule-women-owned-small-business-and-economically-disadvantaged-women-owned-small-businesscertification/#:~:text=By%20Office%20of%20Advocacy%20On,them%20to%20verify%20any%20documentation.19 “Small Business Data Hub,” U.S. SBA, accessed December 2, 2024, https://datahub.certify.sba.gov/.20 “Small Business Data Hub,” U.S. SBA, accessed December 2, 2024, https://datahub.certify.sba.gov/.21 R. Corrine Blackford, The Women-Owned Small Business Contract Program: Legislative and Program History, CRSReport for Congress R46322, (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service [CRS], June 2024);“Federal Procurement Data System Report: FY2018-FY2022,” General Administrative Services (GSA),https://www.gsa.gov/policyregulations/policy/acquisition-policy/small-business-reports.22 Government Accountability Office (GAO), Federal Advertising: Contracting with Small Disadvantaged Businesses and Those Owned by Minorities and Women Has Increased in Recent Years, GAO-18-554 (Washington, DC: GAO, July2018), https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-18-554; “Small Business Program Goals & Performance,” Department ofDefense (DOD), accessed December 2, 2024, https://business.defense.gov/About/Goals-and-Performance/; JasonWiens and Michelle Kumar, “A Look at Women-Owned Small Business Contracting,” Bipartisan Policy Center, October22, 2022, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/women-owned-small-business/.23 “Small Business Data Hub,” U.S. SBA, accessed December 2, 2024, https://datahub.certify.sba.gov/.24 U.S. SBA, Equity in Federal Procurement Literature Review (Washington DC: SBA, November 2023),https://www.sba.gov/document/report-equity-federal-procurement-literature-review#; R. Corrine Blackford, TheWomen-Owned Small Business Contract Program: Legislative and Program History, CRS Report for Congress R46322,(Washington, DC: Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service [CRS], June 2024).25 U.S. SBA, Equity in Federal Procurement Literature Review (Washington DC: SBA, November 2023), 14,https://www.sba.gov/document/report-equity-federal-procurement-literature-review#; JPMorgan Chase & Co., LiftingBarriers to Small Business Participation in Procurement (n.p.: JPMorgan Chase & Co. PolicyCenter2022),https://www.jpmorganchase.com/content/dam/jpmc/jpmorgan-chase-and-co/documents/lifting-barriers-to-smallbusiness-participation-in-procurement-brief.pdf; Minority Business Development Agency (MBDA), The MinorityBusiness Development Agency: Vital to Making America Great (Washington, DC: MBDA, n.d.)https://www.mbda.gov/page/minority-business-development-agencyvital-making-america-great; U.S. Department ofLabor (DOL), Progress in Procurement: Equity in Federal Contracting (Washington, DC: DOL, 2022),https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OPA/blog/equity-in-federal-contracting.pdf.26 Jason Wiens and Michelle Kumar, “A Look at Women-Owned Small Business Contracting,” Bipartisan Policy Center,October 22, 2022, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/women-owned-small-business/; Jessica Dirogene, “FederalProcurement & WOSBs” (master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin, Platteville, 2023),https://minds.wisconsin.edu/bitstream/handle/1793/83852/Dirogene%2C%20Jessica.pdf; Bipartisan Policy Center,From Pandemic to Prosperity: Bipartisan Solutions to Support Today’s Small Businesses (Washington, DC: BipartisanPolicy Center, March 2022), https://bipartisanpolicy.org/download/?file=/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/SmallBusiness-Policy-Report_R01.pdf.27 Daniel Chow, The Probability of Winning Federal Contracts: An Analysis of Small Minority Owned Firms, (Washington,DC: MBDA, June 2022), https://www.mbda.gov/sites/default/files/2022-06/MBDA%20Compelling%20Interest%20Study.pdf.28 Daniel Chow, The Probability of Winning Federal Contracts: An Analysis of Small Minority Owned Firms, (Washington,DC: MBDA, June 2022), https://www.mbda.gov/sites/default/files/2022-06/MBDA%20Compelling%20Interest%20Study.pdf.29 Elaine Reardon, Nancy Nicosia, and Nancy Y. Moore, The utilization of women-owned small businesses in federalcontracting, Rand Corporation Vol. 442, 2007,https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2007/RAND_TR442.pdf.30 Elaine Reardon, Nancy Nicosia, and Nancy Y. Moore, The utilization of women-owned small businesses in federalcontracting, Rand Corporation Vol. 442, 2007,https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2007/RAND_TR442.pdf.31 Daniel Chow, The Probability of Winning Federal Contracts: An Analysis of Small Minority Owned Firms, (Washington,DC: MBDA, June 2022), https://www.mbda.gov/sites/default/files/2022-06/MBDA%20Compelling%20Interest%20Study.pdf.32 Mikaella Polyviou, Leopold Ried, and Robert Wiedmer, “Selection of Small and Diverse Suppliers and ContractualPerformance: Do Set-Asides Pay Off?” Production and Operations Management, July 26, 2024,https://doi.org/10.1177/10591478241265646.33 Chris Parker and Dwaipayan Roy, "A granular examination of gender and racial disparities in federalprocurement," Data & Policy 6 (2024): e25, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4714527.34 U.S. SBA, Equity in Federal Procurement Literature Review (Washington DC: SBA, November 2023),https://www.sba.gov/document/report-equity-federal-procurement-literature-review#; Rhonda Lynn Johnson,“Identifying Barriers Influencing Federal Government Contracts for Women-Owned Small Information TechnologyCompanies” (dissertation, University of Phoenix, 2015), ProQuest. 35 U.S. SBA, Equity in Federal Procurement Literature Review (Washington DC: SBA, November 2023), 15-17,https://www.sba.gov/document/report-equity-federal-procurement-literature-review#.36 Justin Bateh and Shawna Coram, “Federal Procurement & Women-Owned Small Business: A Systematic Review onBarriers to Participation in Government Procurement Contracts,” Southern Business & Economic Journal (2022): 63–85;Sergio Fernandez, Deanna Malatesta, and Craig R. Smith, "Race, Gender, and Government Contracting: DifferentExplanations or New Prospects for Theory?" Public Administration Review 73, iss. 1 (2012): 109-210,https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02684.x37 U.S. SBA, Equity in Federal Procurement Literature Review (Washington DC: SBA, November 2023),https://www.sba.gov/document/report-equity-federal-procurement-literature-review#.38 Justin Bateh and Shawna Coram, “Federal Procurement & Women-Owned Small Business: A Systematic Review onBarriers to Participation in Government Procurement Contracts,” Southern Business & Economic Journal (2022): 63–85.39 Bipartisan Policy Center, Supporting Small Business and Strengthening the Economy Through Procurement Reform(Washington, DC: Bipartisan Policy Center, July 2021); https://bipartisanpolicy.org/download/?file=/wpcontent/uploads/2021/06/Small-Business-Report_RV1-FINAL.pdf.40 U.S. SBA, Equity in Federal Procurement Literature Review (Washington DC: SBA, November 2023),https://www.sba.gov/document/report-equity-federal-procurement-literature-review#.41“USASpending (2019–2021) The Official Source of Government Spending Data”, USASpending, accessed December 2,2024, www.usaspending.gov/42 “Data Dictionary,” USASpending, accessed December 2, 2024, https://www.usaspending.gov/data-dictionary.43“Federal Procurement Data System,” FPDS, accessed December 2, 2024,https://www.fpds.gov/fpdsng_cms/index.php/en/.44“October 2024 Data Dictionary,” System for Award Management, accessed December 2, 2024.45“ABS Tables,” U.S. Census Bureau, accessed December 2, 2024, https://www.census.gov/programssurveys/abs/about.html.46“American Community Survey Data,” U.S. Census Bureau, accessed December 2, 2024,https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data.html.